Searching Holocaust Records for My Grandmother’s Story

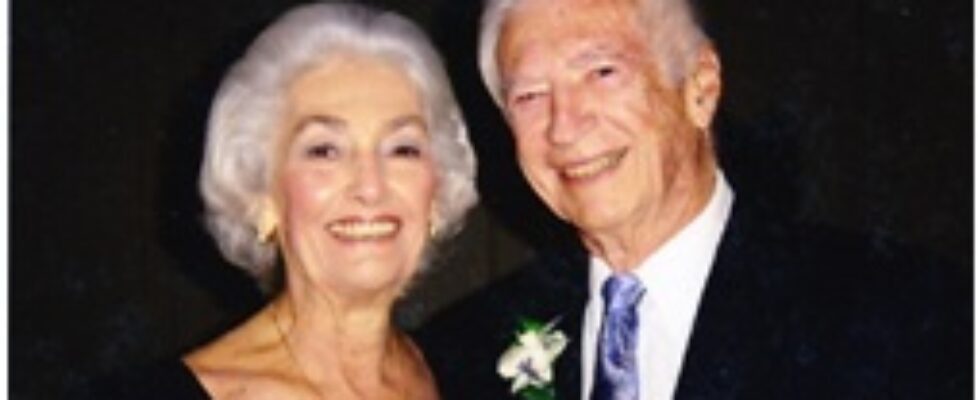

Irv Adler, the Temple’s Treasurer, traveled to Vienna recently to place a Stone of Remembrance in front of the home where his grandmother Clara Bader Nichtern lived before she was killed by the Nazis. Through extensive research that he continues today, Irv learned that his grandmother was murdered in June 1942 at the Maly Trostinets death camp outside of Minsk. We’re sharing the remarks he made during the commemoration on May 18, 2014. Find more in the August Bulletin.

I was born in 1943 and grew up with my family and extended family in the upper west side of New York City, which – based on what I understand today – was sort of a Vienna transplanted. I never heard the word “Holocaust” until probably sometime in the 1980s. As I got older, I realized that I had European parents. And then I realized that I had Viennese parents. And then I realized that everyone in my family came from Vienna. Other than the fact that they all came from Vienna and that Vienna was a great European city, I had no clue what this meant.

Sometime, I don’t recall exactly when, I found out that my maternal grandmother never got out of Europe and was killed by the Nazis. I had no idea when she died or where she died; and whenever I had a conversation with my mother about this, the conversation was very short, as my mother would become very emotionally distraught and couldn’t talk about anything.

My mother, Elsa Nichtern, left Vienna in September 1938. She went to England and then, two years later, she came to America. When my mother left Vienna, she took her aunt with her, fully expecting to get her mother, Clara Bader Nichtern, out of Vienna also. That never happened. My mother carried that burden with her, her entire life.

As I was growing up, I got bits and pieces of the story at various times, but never any details of what had happened in Vienna or why the people I knew and met growing up were here in America. And I knew virtually nothing about the family members who didn’t get out.

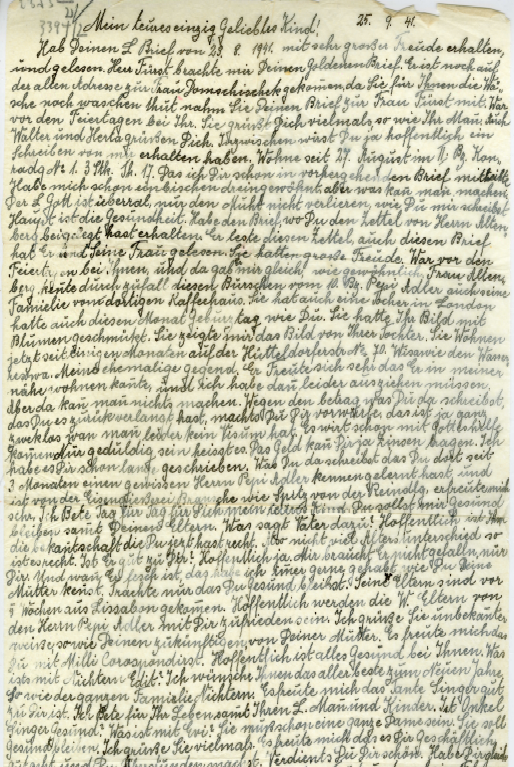

My mother and father moved to Florida in 1974. In 1996, my father passed away. My mother and I decided it was time to move her from her condo to an independent-living facility. It was during this move that I discovered a leather-bound suitcase that could have been used as a prop on the set of Casablanca. It contained photo albums and various papers relating to my parents and other family members– and a small, tightly wound pack of letters, tied with a pink ribbon, in an old and somewhat yellowish plastic pouch with a zipper on top.

About one year later, during a visit to my mother’s independent-living facility, I sat down with her. We took out the suitcase, pulled out some old photo albums and I finally got her to provide some more details on her mother and other family members, many of whom I never knew or had even heard of.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but my mother, who was 87, was starting to lose her mental faculties. Shortly thereafter, my mother had a stroke and lost her ability to speak. My mother passed away in December 2003. (Photo: 1932: Irv’s mother and grandmother.)

In August of 2010, my wife, Fran, and I took a vacation to Europe, which included stops in Prague, Budapest and Vienna. We got to Vienna late in the afternoon of Sunday, August 8, 2010, and decided to see the Holocaust Memorial at Judenplatz. We noticed a small museum in a corner of the plaza. We entered and looked around. In the museum shop, a woman was sitting behind a counter which had literature about the Viennese Jewish community. I struck up a conversation with the woman and told her that my Viennese grandmother had been killed during the Holocaust and asked her where I could get some more information about victims of the Holocaust. She said we should go to the DOEW (Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance).

At 9 AM the next day, we were at the DOEW. We were greeted by an elderly woman. We told her we had no appointment and why we came to the DOEW. A few minutes later, we were escorted to an office where we first met Dr. Elisabeth Klamper, the DOEW archivist. After about 15 minutes of searching through the DOEW records, Dr. Klamper raised her head from behind the computer screen. Her face had lost its color. She said, “I have some very bad news to tell you. Your grandmother was killed at Maly Trostinets.” I had no idea what she was talking about, since I had never heard of Maly Trostinets. Dr. Klamper gave us a brief rundown of the Maly Trostinets extermination camp. Since then I have learned a great deal more. I now know more about my grandmother’s life and how she came to live in Leopoldstadt. I now know that my grandmother was murdered in June 1942 at the Maly Trostinets death camp outside of Minsk.

After we met with Dr. Klamper, what originally was planned as a five-day vacation resulted in 2½ days of researching at the Israelische Kultesgemeinde (IKG) and the Archives of the City of Vienna to find out everything I could about my family.

When we returned to our home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, I pulled out the suitcase with the letters. I opened the plastic pouch and took out the bundle of letters and started to remove the letters from the tightly wound bundle: one by one and very carefully. Some were damaged, but most were in good shape. Some were on conventional writing paper. Some were on very thin tissue paper. Some were about the size of a standard piece of typing paper. Some were about twice that size. Most had multiple authors. Most were completely covered with writing. There were about 100 letters written from 1938 to 1941.

At this point, I didn’t quite know what I had. But I knew enough to realize that the letters could represent a diary of my grandmother’s life under Nazi occupation. I knew that I had to get them translated. After about 1 year trying to find a translator, and as a result of my wife’s involvement with a Fort Wayne Holocaust education group, we met Joy Gieschen, a graduate student at a local university, who agreed to take on the translation project. Joy studied German as an undergraduate student and had recently returned to the USA after spending 1 year in Austria. At the time of our meeting, Joy was pursuing a master’s degree in education, preparing for a career as a German teacher.

At this point, I didn’t quite know what I had. But I knew enough to realize that the letters could represent a diary of my grandmother’s life under Nazi occupation. I knew that I had to get them translated. After about 1 year trying to find a translator, and as a result of my wife’s involvement with a Fort Wayne Holocaust education group, we met Joy Gieschen, a graduate student at a local university, who agreed to take on the translation project. Joy studied German as an undergraduate student and had recently returned to the USA after spending 1 year in Austria. At the time of our meeting, Joy was pursuing a master’s degree in education, preparing for a career as a German teacher.

Joy became very involved with the letters and asked if she could use the translated letters as the basis for her master’s degree research project. As Joy was discovering information about my grandmother, it started to become clear that possibly the letters could form the basis of a larger research project and even a broader-based Holocaust research publication. With this in mind, we decided to go back to Vienna; back to the DOEW; back to the IKG; and to visit the places where my grandmother lived. So in June 2012, Fran, Joy and I traveled to Vienna.

As fate would have it, Joy was actively looking for a job during spring 2012. One of the job possibilities was teaching at an international school in Vienna. Joy made arrangements to go there for a preliminary interview when we were in Vienna. We decided to go with her. As we were leaving the school, we mentioned that our main reason for the Vienna trip was to do research on the “Letters” project. One of

As fate would have it, Joy was actively looking for a job during spring 2012. One of the job possibilities was teaching at an international school in Vienna. Joy made arrangements to go there for a preliminary interview when we were in Vienna. We decided to go with her. As we were leaving the school, we mentioned that our main reason for the Vienna trip was to do research on the “Letters” project. One of

May all their memories be for a blessing.

Utilizing the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards enables Andy and Janet to ensure that the products and processes they are using to construct their home can be independently verified as truly “green.” This new home will not only enable them to live with a smaller carbon footprint, but they will be able to grow much of their own food. In addition to fruits and vegetables, they plan to have beehives and perhaps a few chickens.

Utilizing the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards enables Andy and Janet to ensure that the products and processes they are using to construct their home can be independently verified as truly “green.” This new home will not only enable them to live with a smaller carbon footprint, but they will be able to grow much of their own food. In addition to fruits and vegetables, they plan to have beehives and perhaps a few chickens.

Though Green Oak Farm will be primarily their home, Andy and Janet are committed to making the house and property a community resource for education and advocacy for improved sustainability in Northeast Indiana.The construction of the home is now well underway. Andy and Janet anticipate that the roof will be on by Thanksgiving and the windows will be in place by Hanukkah. They hope to be able to move into the home late next summer and are looking forward to building a Sukkah in the backyard next fall.

Though Green Oak Farm will be primarily their home, Andy and Janet are committed to making the house and property a community resource for education and advocacy for improved sustainability in Northeast Indiana.The construction of the home is now well underway. Andy and Janet anticipate that the roof will be on by Thanksgiving and the windows will be in place by Hanukkah. They hope to be able to move into the home late next summer and are looking forward to building a Sukkah in the backyard next fall.

_opt.jpg)

A Jew by choice, Bruce said he’s always enjoyed studying Torah and found it inspiring because “it’s the world’s wisest poetry.” He said it’s particularly meaningful to study the text directly rather than a translation because the nuances are so important. The discussion prompts him to explain particular illusions that appear in the passage and why he needed to clarify the meaning of a verb. He also patiently explains lexical themes and poetic figures of speech such as anaphora (repetition of a word or phrase) that help to fully appreciate and comprehend the portion.

A Jew by choice, Bruce said he’s always enjoyed studying Torah and found it inspiring because “it’s the world’s wisest poetry.” He said it’s particularly meaningful to study the text directly rather than a translation because the nuances are so important. The discussion prompts him to explain particular illusions that appear in the passage and why he needed to clarify the meaning of a verb. He also patiently explains lexical themes and poetic figures of speech such as anaphora (repetition of a word or phrase) that help to fully appreciate and comprehend the portion.

Bruce became fascinated with the story and the controversy provoked by the film. He still teaches the films course each spring at Canterbury, but he no longer shows “Playing for Time” because he says it misrepresents the story.

Bruce became fascinated with the story and the controversy provoked by the film. He still teaches the films course each spring at Canterbury, but he no longer shows “Playing for Time” because he says it misrepresents the story.

“What was most meaningful about this project was to let the world know what happened – most people don’t know there were 20,000 Jews at Shanghai,” she said.

“What was most meaningful about this project was to let the world know what happened – most people don’t know there were 20,000 Jews at Shanghai,” she said.

Rabbi Meir said the production team – Cinematographer Ty Black from Bokeh Film & Video and Producer Joe Collins – and Cantor Shore and Bob Nance provided guidance in developing the plan.

Rabbi Meir said the production team – Cinematographer Ty Black from Bokeh Film & Video and Producer Joe Collins – and Cantor Shore and Bob Nance provided guidance in developing the plan.

The most intricate part of the production came for Kol Nidre when six congregants each held a Torah in a line on the bimah though they never actually were in the room together. They were recorded at different times and united by an intricate plan and seamless editing.

The most intricate part of the production came for Kol Nidre when six congregants each held a Torah in a line on the bimah though they never actually were in the room together. They were recorded at different times and united by an intricate plan and seamless editing.